Introduction

I had a rather long break from writing blog posts, but it has not been due to inactivity, quite the opposite! The good side of this busy period is that there is a large backlog of new topics to write about on this blog.

I had a rather long break from writing blog posts, but it has not been due to inactivity, quite the opposite! The good side of this busy period is that there is a large backlog of new topics to write about on this blog.

This week I wanted to draw attention to the book that my former colleagues and I wrote, and which was recently published. It is great to finally have it in my hand! The book is about the discovery of the Higgs boson at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

What is the Higgs boson?

So what exactly is a Higgs boson? Well, as the name implies, it is a particle of type boson.

There are two types of particles in the Universe, fermions and bosons. That is it, there is no third type!

Matter consists of fermions.

Bosons, on the other hand, carries the forces between particles.

A long time ago, Peter Higgs and some other smart people proposed that there is a field everywhere in the Universe, and that particles interact with this field all the time.

Since then we call this crazy idea the Higgs field.

According to theory, the Higgs field gives mass to elementary particles.

Without the Higgs field, elementary particles would not have any mass, and the world would not exist as we know it.

The Higgs boson is an excitation of the Higgs field, similar to how a wave is a ripple on a pool of water.

In a matter of speaking, we are searching for waves to conclude that there is water nearby, so by finding the Higgs boson we know that the Higgs field exist.

Sometimes I hear people saying that the Higgs boson is responsible for all mass in the Universe.

While this is true for elementary particles, you cannot blame the Higgs boson if you are overweight, since most of your body mass comes from atoms and atoms are not elementary particles.

Atoms consist of protons and neutrons, who in turn consists of quarks, and it is the forces that holds them together that is the source of most of the visible mass.

I say visible here, because cosmology tells us that there is also dark matter, which we frankly have no clue about what it is.

How we discovered it

Heavier particles interact more strongly with the Higgs field, and in fact the mass of the particle is created through the Higgs mechanism.

This means that a Higgs boson is more likely to decay to heavier particles rather than light ones, and this property played a major role in how we set up our Higgs hunting strategies.

The heavy decay products are very short lived and also decays into lighter particles.

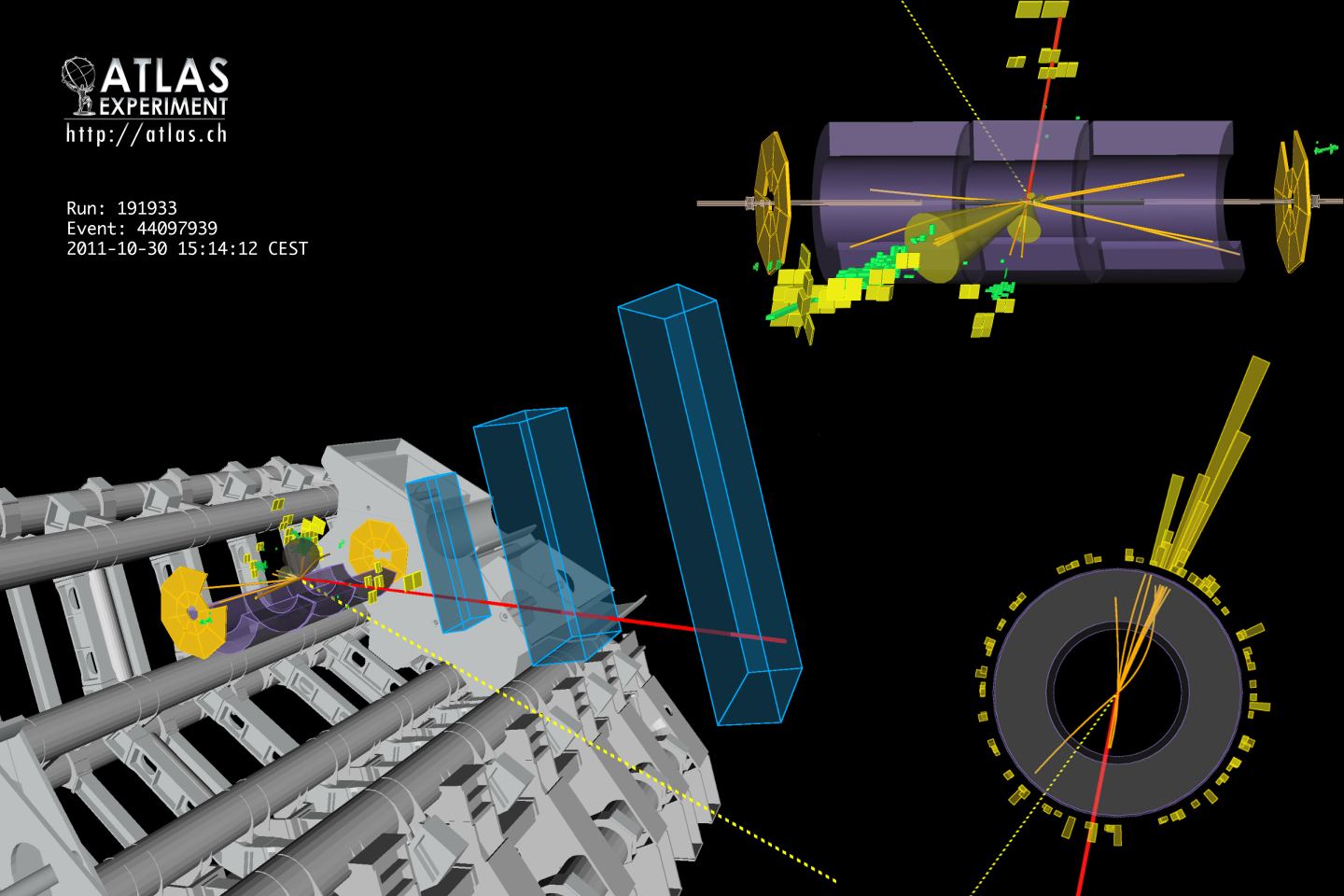

The result can look like the picture I made below a few years ago, where a Higgs boson candidate decays into two W-bosons, one W-boson decays to a pair of quarks, the other into a muon-neutrino pair.

Since we cannot see the W-bosons directly, much less the Higgs boson itself, we have to look for final state particles that are creating signatures in the detector that could mean that a they were produced by a decaying Higgs boson.

When you take into account that we collected about 40 TB of data per second, finding a needle in a haystack does not even come close to describing the challenge.

To process all this data CERN developed a distributed computing called the GRID which was absolutely crucial to the success.

Another strategy is to select an extremely rare combination of final state particles where also the false positives, the background noise, is heavily suppressed.

Regardless of the strategy of each individual Higgs hunter group, having a thorough understanding of the background noise was of very high importance.

To understand what we should expect to see in the case the Higgs boson did not exist (the null hypothesis), we frequently turned to Monte Carlo simulations.

The simulations were in turn validated by special minimum bias streams in the data collection and a whole battery of tests and scrutiny.

In practice we did not limit ourselves to only one strategy, but we did all of them at once, and combined all the results into one confidence interval to rule them all.

And with success too: On 4 July 2012, the ATLAS and CMS experiments at CERN's Large Hadron Collider announced they had each observed a new particle in the mass region around 126 GeV.

This particle is consistent with the Higgs boson predicted by the Standard Model.

The year after, the Nobel Prize was awarded for the discovery of the Higgs boson.

Importance of the discovery

The Higgs boson was the final missing particle in the Standard Model of particle physics.

It unifies three of the four forces of the Universe, the Strong force, the Weak force and Electromagnetism. (Sorry Gravity, you are just too weird to fit in at this party.)

If we had concluded that the Higgs field does not exist this entire house of cards would have collapsed and we would have had to admit that we know nothing and start all over again.

So what can we do with this newfound knowledge? Sadly we do not have any business use cases just yet.

Then again, we did not plan on using GPS when Einstein discovered the theory of relativity.

Nor did we think of mobile phones when electricity was discovered, or Netflix when CERN invented the World Wide Web for that matter.

While the Higgs bosons was the last piece of a very complex puzzle, we know it is not the end.

For example, neutrinos have always been a poor fit to the Standard Model. They should be massless, yet they aren't...

Where did all the anti-matter go? And what is all this dark matter anyway?

It looks like Nature has not yet revealed all her secrets to us.

The book is available for purchase at World Scientific